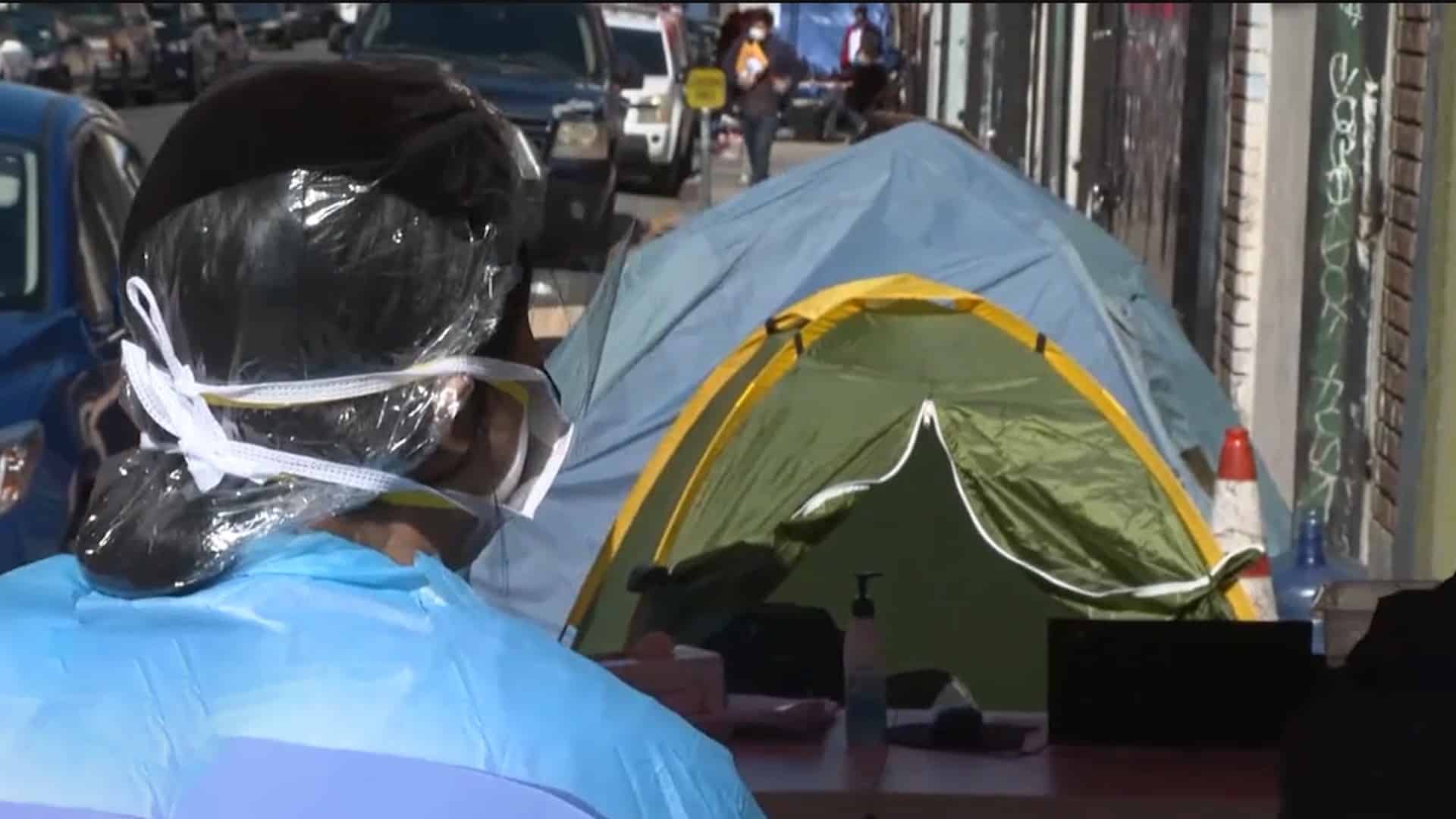

One evening around dusk, a group of older men and women shuffled into a line. They waited patiently as their temperatures were taken, names jotted down, and each assigned a place on the cold concrete, their bed for the night.

As I wrapped up a day in clinic, my eyes scanned this group and wondered what each one thought about as they waited in yet another line. How many other lines had they waited in just that day for their basic needs to be met? A life lived in lines.

As a nurse practitioner caring for patients through street medicine in Los Angeles, I see these lines every day. But the truth is, each person in line isn’t just another “underserved” person waiting for resources. Each man and woman has a story, each has hopes, each has experienced trauma, and each has incredible resilience. They are my teachers, my friends, a father, mother, son or daughter.

I remember meeting “Sally” during street rounds a few months ago. Sally had a kind face and a calming voice. Sally had lost her job, became homeless and had been on the streets for 10 years. She had learned over the last decade to survive, to keep to herself, access resources only when she needed to, and be a blessing to others when she could. But Sally was also dying. A tumor eroded her body and she didn’t know why or how to get help. So she pressed on, waiting in lines patiently, sleeping on the ground night after night, suffering through the pain.

See, the lie is that at any time “these people” can turn things around, somehow step out of that proverbial line and decide they no longer want to be ill, or poor, or homeless, or struggle with addiction or mental illness. That the onus is all on them to just make the right decision.

This is a lie — a lie of borne out of privilege.

The responsibility is ours. Those of us making decisions, whether in healthcare, social services, housing authorities, insurance companies, policymakers, emergency services, or mental health services. It’s on us to examine our ways and ask ourselves the harder question: where have we failed?

Many of us had hoped that this public health emergency would be the wake-up call that would remind us of the reality that we have already been in a state of emergency.

But so far, COVID-19 has revealed one major truth: it’s not enough. All the millions of dollars, the time, resources, planning, still aren’t enough to address the state of emergency in our vulnerable communities. It’s not enough to prevent communities of color and people in poverty from dying at rates 4 times higher than other communities in Los Angeles.

It’s not enough.

Even as we saw resources pour in – revealing news reports, hotel rooms turned into housing, all to combat the pandemic in vulnerable communities because we realized that this new experience of suffering actually impacted us all. We could no longer turn our heads away from the fact that the same danger that threatened the lives of all those nameless, poor people standing in lines threatened ours as well. And it impacted our neighborhoods, impacted where we shop, impacted where we worship, impacted where our children play and more — all because the virus could spread to anyone, anywhere — it didn’t care about your credit score or the color of your skin.

But now, we are in “recovery.” The larger system has recovered from the pandemic and we can now rebuild our lives and continue on. Or so they say.

And yet, the state of emergency for our most vulnerable communities remains unchanged. The rates of homelessness are on the rise in Los Angeles, 14.2% increase in 2019 and Black people are 4 times more likely to experience homelessness than members of other race and ethnicity groups.

So what does “recovery” look like for people who still have no homes to live in, who still have no reliable access to healthcare, who still struggle with debilitating mental illness or addiction? Who are trafficked, targeted by drug cartels or immigration raids and who fight to survive another night – night after night?

When do they get to recover?

Recovery is a word of privilege. You get to recover because you have the privilege to recover, to move on, to reopen. This privilege even allows you to choose to not wear a mask because you find it inconvenient.

Communities experiencing homelessness or living in poverty don’t have this same privilege. The pandemic there rages on even if it’s no longer in the headlines or in the subject of funding proposals. The pandemics of racism, unfair policing, mass incarceration, gang violence, defunded education systems, and lack of affordable housing – these carry on, relentlessly. Unfettered by words and actions of those “in recovery.”

We are tired of waiting in line for our recovery. We’ve been waiting a long time.

We must be a community of people who understand our privilege as well as our inter-connectedness. Recovery is only truly achievable when it is a reality for all.

We can’t say we have recovered as a community when in Los Angeles, 227 people per day still fall into homelessness or when for every 100,000 people, 15 who are White will die from coronavirus, while a staggering 52 who are Native American or Pacific Islander will perish.

No we are not in recovery.

Let us not recover too soon. The system is still sick and broken and in need of healing.

So let us instead uncover.

Let’s uncover the lies that undergird our policies and systems, which make people poor and keep people poor. Let’s uncover the truth about where funding for affordable housing is currently going and where it should be going. Let’s uncover the injustices that formerly incarcerated men and women face as they try to re-enter society. Let’s uncover the need for more funding in mental health services, substance use recovery programs and interim housing. Let’s uncover the need for more meaningful, collaborative relationships between policymakers and grassroots organizers.

Let’s uncover the perseverance and strength in vulnerable communities and recognize their impact, their worth and their voice.

Let’s uncover the biases in our own hearts that make it easier for us to close our eyes to the suffering of others.

And let us uncover a path toward true community — a way of living together that doesn’t find us forging ahead for our own recovery, but instead finds us, restored, rebuilt and revived.

Sally died a few weeks ago. Warm in her bed, surrounded by her family of case managers and nurses who had been caring for her since we got her off the streets. Her story is one of thousands in need of a system that restores hope and dignity, even in death. Let this be our true legacy.

Hyperlinks for references:

http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/phcommon/public/media/mediapubhpdetail.cfm?prid=2443

https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/LACountyHomeless-COMPLAINT.pdf

Author Bio:

Shannon Fernando is a California board-certified family nurse practitioner who has devoted her career to increasing access to healthcare for vulnerable people and communities. Shannon serves as Chief Innovations Officer at Los Angeles Christian Health Centers in LA’s Skid Row community, providing primary care for individuals experiencing homelessness and driving strategy and vision for new programming, including their robust street medicine program. She previously served the Los Angeles homeless population through the St. Vincent Cardinal Manning Center as an AmeriCorps scholar. Shannon holds degrees from the University of California, Los Angeles and Azusa Pacific University.